Claustrophobia is something most people struggle with, even if they don’t really think they do – nobody is comfortable being trapped in a small space for hours on end. Suffering through a global pandemic, meanwhile, is something we can all definitely relate to, and Tin Can, the latest offering from Canadian filmmaker Seth A. Smith (The Crescent) combines both universal fears into a compelling, discomfiting, and ruthlessly inventive little sci-fi chiller. There’s a deadly infection ravaging the world but, despite everything that she’s doing to fight back against it, a brilliant scientist finds herself trapped in the titular, well, tin can.

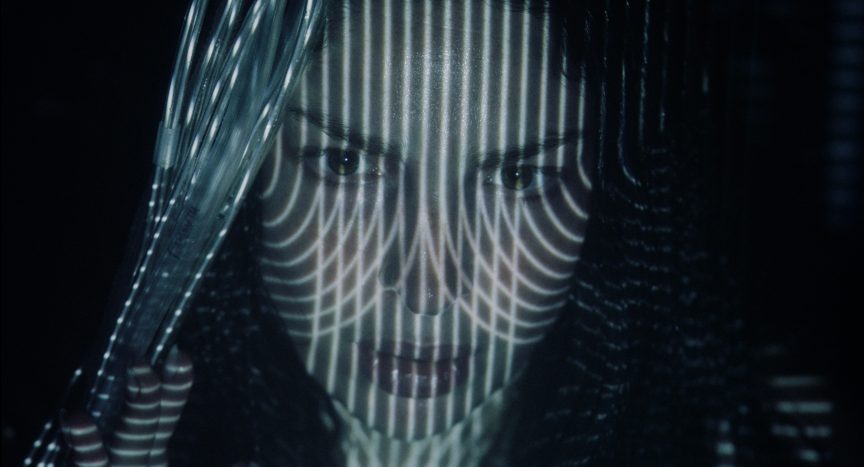

Anna Hopkins is Fret, the lead parasitologist at the kind of aggressively beige, violently modernist building that only seems to exist in Canadian horror movies. She’s working hard to find ways to combat the effects of Coral, a seemingly untreatable disease, and is on the brink of a breakthrough when Fret is attacked and drugged, waking up intubated in a life-suspension chamber. It’s a visceral moment, wires and tubes coming out of every orifice, and Hopkins plays it to perfection considering the actress’s feet are also in a few inches of water, which can’t have been comfortable. Smith keeps the camera tight on her face to emphasize the claustrophobia, drifting down every now and again to take in gross, floating feet peelings in the water, for instance.

Tin Can is certainly set in Cronenberg’s Canada and in fact the film would make a lovely companion piece to his son, Brandon’s, recent Possessor, which boasted a similar through-line in mind-bending scientific malfeasance. The great man’s influence is keenly felt, but then again when is it not, particularly in homegrown fare? Michael Ironside even shows up in a small part, looking a bit like Harvey Weinstein when we first meet him before being placed in a far more vulnerable state. Smith’s story is highly original, however, from how it plays with the format to its non-linear plot structure, which fills in Fret’s backstory with her partner without the need for energy-sapping exposition.

Although Fret’s predicament is the starting point for the story, Tin Can widens its scope to become something altogether slipperier and more difficult to compartmentalize. It’s a story of survival, of one woman’s fight back against an unknowable force, but this is also a rumination on humanity and the nature of existence, meaning the film is a bit of a downer at times. Smith wears many different hats, including handling the score, but leaves the SFX to the brilliant Allan Cooke, who conjures up incredibly disgusting makeup and prosthetics to show the weirdly bubbly effects of the virus. The body horror is tactile, practical, and stomach-churning throughout, but that visceral sense of place extends to the huge boilers in which several unlucky characters are placed – their tin cans, as it were – as well as the outer world, which feels like ours but also retains a sense something is off balance.

There’s a lovely texture to Tin Can, cinematographer Kevin A. Fraser taking a painterly approach to the nightmare scenario conjured up by Smith and co-screenwriter Darcy Spidle. This is a horror show, no doubt about it, but it’s consistently stunning to look at, the deep blacks, golds, and silvers introduced early on subsequently coinciding with cyborgs whose existence is left crucially unexplained. Ironside’s Santa beard pops under strategically placed blacklights, his booming voice unmistakable in the suffocating darkness. There’s a great amount of care and attention paid to the little details, creating an immersive experience it’s difficult to recover from. Still, everything is anchored by Hopkins’ charismatic, committed performance in the lead role.

Related: Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes [Fantasia 2021 Review]

Fret is in essentially every scene, whether she’s fighting to get out of her tin can, fighting to find a cure, or fighting to save her relationship. The actress looks completely different in the film’s flashback sequences, despite not having the ease of a different haircut or pair of glasses or something. Hopkins imbues her performance with a sad knowingness, communicating a wide range of emotions with a simple look. Fret is not a superhero or a wronged woman out for vengeance; she’s simply a well-meaning scientist being punished for doing her best who refuses to accept her fate lying down. There are layers to her predicament that gradually reveal themselves, but Fret, clearly named as such on purpose, is never completely opaque as a character. There’s a sense that she doesn’t even fully know herself, in fact.

Fret is the anchor of this impressively human story which, despite its grand themes and jaw-dropping visuals, is at its core a tale of love gone wrong and female ambition being held back by jealous, petty men. Tin Can might seem, on its surface, like another take on something like Buried or this year’s impressive Netflix thriller Oxygen, but it’s something far less open to easy classification, much to Smith’s great credit. There may be a confined space and a trapped character fighting for their life, but the real threat at the core of Tin Can’s dark, metal heart is more insidious and deeply entrenched in our current landscape than we’d care to admit. As a result, it’s a remarkably affecting experience that’s difficult to shake, particularly considering our own global health crisis is far from over.

WICKED RATING: 8/10