Horror is evolving as a genre. Although your local multiplex is still loaded with the usual contenders, look a bit closer and you’ll find the latest drama, thriller, or crime offering is closer to horror than you might expect. In this bi-weekly series, Joey Keogh presents a film not generally classified as horror and argues why it exhibits the qualities of a great flight flick, and therefore deserves the attention of fans as an example of Not Quite Horror. This week, it’s Steve McQueen’s take on the legend of Bobby Sands in Hunger.

From Shame to 12 Years A Slave, filmmaker Steve McQueen (no, not that one) has a lot to say about men in various stages of struggle. Whether it’s being enslaved by one’s addiction to the lusts of the flesh, or being quite literally enslaved, McQueen knows how to put us into the shoes of the tortured. But what happens when that torture is self-inflicted?

McQueen’s brutal, bruising and quite brash Hunger, which chronicles the imprisonment of real-life Irish republican activist Bobby Sands and the hunger strike that would eventually lead to his death after 66 horrific days, is, in many ways, his most traumatic and scarring case study–freed of Shame‘s style and Slave‘s necessarily sickening humanism.

McQueen presents Sands as a man utterly convinced of the courage of his convictions, his bemused cell-mate marvels at him with wide eyes as though he’s worried this caged animal might unleash all that pent-up rage at any time. However, Hunger doesn’t stick around long enough for us to get a real handle on Sands, the man. It’s more interested in Sands, the activist.

In a now-legendary 17-minute continuous shot, set in one, bare room, Sands meets with his parish priest to discuss the planned hunger strike. Utilising an anecdote about a dying doe, whom he put out of its misery as a child, Sands tries to convince the holy man that what he’s planning to do is murder, rather than suicide.

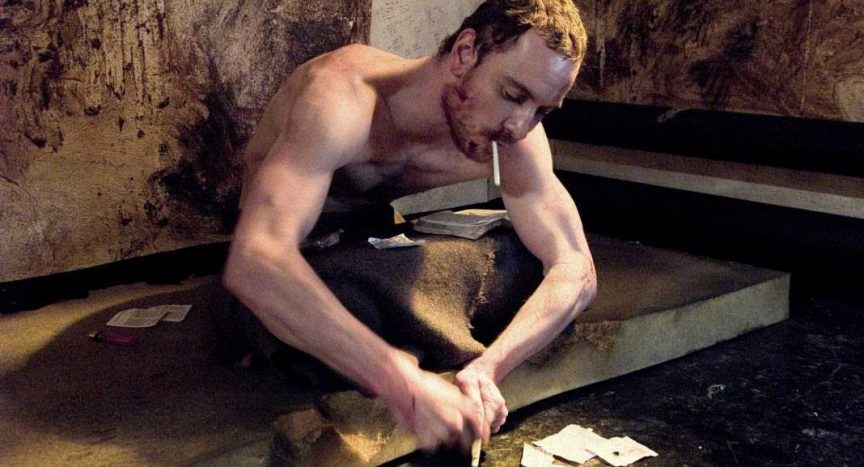

It’s a stark, utterly captivating scene in which Michael Fassbender (then a relative unknown), as Sands, and veteran Irish character actor Liam Cunningham give a masterclass in performance and inhabiting difficult characters, plagued with demons, trying to do right by themselves and each other. McQueen doesn’t necessarily ask us to sympathise with either, just to listen.

Once the strike kicks off, Hunger really treads into Not Quite Horror territory, as Sands’ self-imposed torture is displayed in all its horrifying glory. Fassbender, reduced to skeletal proportions, is carried from bed to toilet to bath. In one, horrifying moment, he is left to fall to his knees by a medical professional from the other side of the divide.

Once the strike kicks off, Hunger really treads into Not Quite Horror territory, as Sands’ self-imposed torture is displayed in all its horrifying glory. Fassbender, reduced to skeletal proportions, is carried from bed to toilet to bath. In one, horrifying moment, he is left to fall to his knees by a medical professional from the other side of the divide.

As he hits the tiled floor with a sickening thud, we almost expect McQueen to pull back and reveal his knees have cracked but Sands is made of sterner stuff than most. We might baulk at his conviction to the cause (the strike led to major political change, but more died before anything concrete happened) but there’s no denying Sands’ bravery.

The scariest element of all, then, is the idea of believing in something so completely, one is willing to give one’s life to it. And McQueen, and Fassbender, present this idea with unflinching, ugly, utterly committed conviction.