Note: This article contains SPOILERS for the films Apartment 1303 (2007) and Apartment 1303 3D (2012).

America used to love remaking Japanese horror films. The Ring and The Grudge have become staples of American horror cinema, and inferior films such as Pulse (2006) and One Missed Call (2008) are also well-known amongst horror fans. While America’s love affair with Japanese horror has died down in recent years, every now and then we get a new film that pays homage to the Japanese remake tryst. One of those films is Apartment 1303 3D (2012).

In the original 2007 Japanese film, lead character Mariko struggles to figure out why her sister Sayaka committed suicide after moving into an apartment on the 13th floor of her new building. She discovers that the place has been host to a rash of suicides after the first tenants, Yukiyo and her mother, both died there.

The American remake follows much of the same storyline, though it is nowhere as good as the original (as in, if it weren’t for this article, I would have stopped watching it after the first 15 minutes). However, I believe there is value in comparing the two for what it tells us about how horror is experienced in these diametrical cultures.

Here are four dichotomies between Japanese and American culture that I noticed in comparing these two films:

Implication vs. Exposition

It’s an oft-heard complaint that American films explain themselves too much and don’t allow the audience to glean information for themselves. This is something I noticed in the American version of Apartment 1303, where this trope is taken to the extreme. The night Janet moves in to her new apartment, she starts hearing strange sounds and spends a good ten minutes of the film talking to herself about what she’s thinking, feeling, and going to do next. I absolutely hated this. In the Japanese film, characters didn’t need to monologue their thoughts. Their feelings were clearly written on their face. Character expression was used to convey thought and emotion, and it was assumed that the audience was smart enough to figure out what was going on for themselves.

Character history was also woven into the film much more organically in the original version. In both films, there was drama between mother and daughter—in fact, this was the central theme around which the film revolved—but the drama wasn’t so explicitly explained in the original. We could see the tension in the characters’ faces when mother and daughter are near each other; we can understand that it’s not a healthy relationship by the way they look at (or refuse to look at) each other. In contrast, the American film pretty much laid out the entire background of mommy issues in the first fifteen minutes, TELLING us that the mother was an abusive alcoholic instead of letting us SEE it in the way they interact with each other.

Devil’s Advocate: There is a part in the Japanese movie where something is explicitly explained. Mariko reads a book on the original tenants, the ones who started the rash of suicides, and we are shown exactly what happens in their story through a series of flashbacks. Explanation can be used in Japanese films, just as implication can be used in American ones; but on the whole, the Japanese version of this film tended to imply more than it explained.

Group vs. Individual

In the American version, Janet is home alone when she first starts hearing strange noises. Her sister, Lara, is also alone in the apartment when her dead sister starts to haunt her. In fact, the entire cast of the American movie is rather small, and can all be named on less than ten fingers.

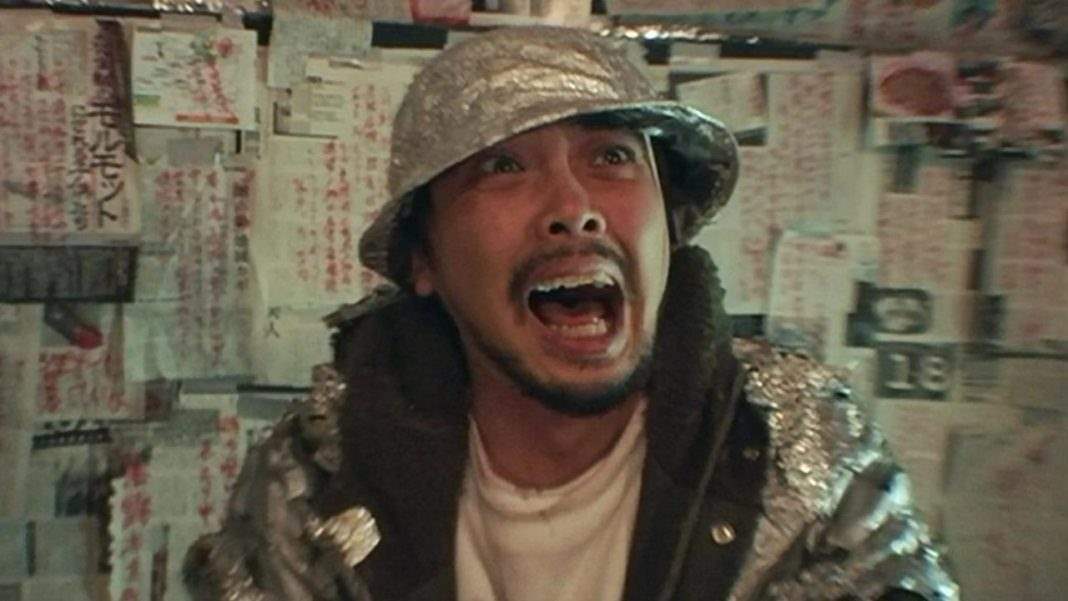

In stark contrast, the Japanese version of the film is constantly full of people. When Mariko’s little sister Sayaka first discovers the ghost, she is having an apartment-warming party with a sizeable group of friends. They all watch her as she’s possessed by Yukiyo’s ghost, and stare on in horror as she all but runs off the balcony. When Mariko first sees Sayaka’s ghost, she is sitting in the apartment with several members of the funeral party. Towards the end of the movie, a new group of tenants has temporarily rented the apartment and are having a party. Yukiyo’s ghost appears, scaring all of them and pushing three of the girls off the balcony to their deaths.

Here they are. All ready to die.

I can’t tell you how many nameless faces appear throughout the Japanese film. The characters seem to constantly be surrounded by groups of people, whereas in the American version only those closest to the main character get any screen time. There isn’t necessarily a right or wrong way to go about populating a scene, but the approach between the two films is certainly very different.

Devil’s Advocate: Mariko spends a lot of time alone in the apartment, experiencing terrifying apparitions, just as Lara does in the American version of the film. Still, there is no doubt that there are simply more people in the Japanese film, as well as more group-oriented activities; whereas in the American version, Lara and Janet pretty much only interact with their mother and Janet’s boyfriend in any significant way.

Invasive vs. Quarantined

Chris Pruett explains this distinction very well in his Guide to Understanding Japanese Horror. (Google it if you’re interested.) It’s a dichotomy that he explains as a fundamental difference between Christianity and the Japanese religions of Buddhism and Shintoism.

In his post, Pruett explains how “the Japanese accept a degree of otherworldliness all around them, while Americans like to concentrate our evil spirits in a specific location (witness our oft-employed “Ancient Indian Burial Ground” cliché). The American approach may be another side effect of Christianity’s tendency to separate everything into absolutes (in this case, defining explicit physical boundaries between “evil locations” and “normal locations”).”

In both films, we definitely have an “evil location”—apartment #1303. This is the central place where all the action occurs. Still, in the Japanese film, the hauntings aren’t confined to the apartment alone. Mariko sees ghosts in the apartment, of course, but also in a bathroom outside the apartment, and in a lobby while talking to the cop. She also hears her sister’s voice through Sayaka’s old cell phone while at home with her mother.

In the interest of full editorial disclosure, I’ll admit that I can’t remember much of what happens in the American version. I swear to God that’s how bad it was. Still, from what I can remember the ghostly apparitions seemed to appear only in the apartment, and maybe throughout the 13th floor. In the American film, the hauntings were largely quarantined to the apartment. This makes it a bit easier to stomach the absurdity of Lara moving into her dead sister’s apartment; based on the Christian expectation that evil spirits are localized to places, Lara would have to physically be present in or near the apartment to see the ghosts. In the Japanese film, this isn’t the case.

Devil’s Advocate: I couldn’t think of one for this section. Like I said, too bad to remember. But the scares in the Japanese version were great!

Softcore vs. Explicit

This is another often-heard comparison between Japan and America: Japan likes “cute” while America likes “sexy.” In reality, what we as Americans consider culturally “cute” may actually be culturally “sexy” to Japanese, so I use the words “softcore” vs “explicit” instead. Both films contain just a smidge of fanservice, but it’s enough that I considered it worth mentioning, especially as another lens through which to view the differences between these two cultures.

There is a very explicit sex scene early in the American film. Janet has just moved into the apartment and has asked her boyfriend Mark to keep her company, as she’s getting freaked out. Not long after he arrives, both their shirts come off and Janet starts talking about how she’s been a “naughty girl” who “needs to be punished.” Mark wastes no time in “punishing” her up against a wall, and then again on top of the couch.

No, the embrace is not as innocent as it looks.

In contrast, the Japanese film has almost no sexual titillation to it… until the last ten minutes or so, when Mariko is confronted with the wrath of Yukiyo’s ghost. Yukiyo’s hair does this crazy thing where it shoots out of her head in tendril-like tentacles, spreading throughout the room and capturing anyone who tries to escape. This time, it catches Mariko’s shirt and slips it off of her shoulder. Look at that bra strap. And then her skirts ride up her legs as she tries to scurry away, showing off those lovely thighs. Score! While she’s nowhere near as naked as Janet and her boyfriend were in the American version, there was still just enough exposure to make it barely sexy.

Now THAT’S my kind of tentacle monster.

Devil’s Advocate: The American “sex scene” isn’t THAT explicit, to be honest. There’s quite a lot of making out, and I’m sure I heard an ass slap at least one; but it does fade to black. Still, it’s a lot more explicit than the bra-strap-audacity in the Japanese film. You definitely know what’s coming after it fades to black. And who.

There were a lot of other comparisons I saw between the films, but I’m afraid a lot of that had to do with the quality of each film in general. As I stated in the beginning, in my personal opinion, the American remake is absolute shit and should be trashed immediately. Go watch the Japanese version! It’s creepy, haunting, dark and gritty, and shows the true horror of what happens when the love between a mother and daughter goes terribly wrong (or worse, isn’t there to begin with).

Still, I appreciate both films for what they can tell us about the differences between horror in these two countries. These are opposites that are often the first to come to mind when talking about “Japan vs. America,” but watching each film back-to-back and seeing the cultural differences come to the fore allows us to appreciate our own cultural understanding of horror, and learn a bit more about someone else’s.